How France invented the censorship-industrial complex

New Twitter Files reveal how French political authorities, NGOs and courts worked to pressure Twitter (now X) into censorship — further consolidating France's post-war censorship-industrial complex

Putting out high-quality journalism requires constant research, most of which goes unpaid, so if you appreciate my writing please consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you haven’t already. Aside from a fuzzy feeling inside of you, you’ll get access to exclusive articles and commentary.

In the United States, the Twitter Files revealed the existence of a vast alliance of government agencies, media organisations, tech companies, academic institutions, and civil society groups working together to remove, flag and suppress disfavoured speech online — a hidden system of narrative control that has come to be known as the censorship-industrial complex.

These practices, however, were by no means limited to the US. The censorship-industrial complex is a global phenomenon, and there’s few places where it holds more sway than in France, as we reveal in a new report for Civilization Works that I co-authored with Pascal Clérotte, and edited by Michael Shellenberger and Alexandra Gutentag.

Indeed, new Twitter Files made available to us reveal how French political authorities, NGOs and courts worked to pressure Twitter (now X) into censorship and proactive moderation or prebunking, despite French law prohibiting preemptive censorship.

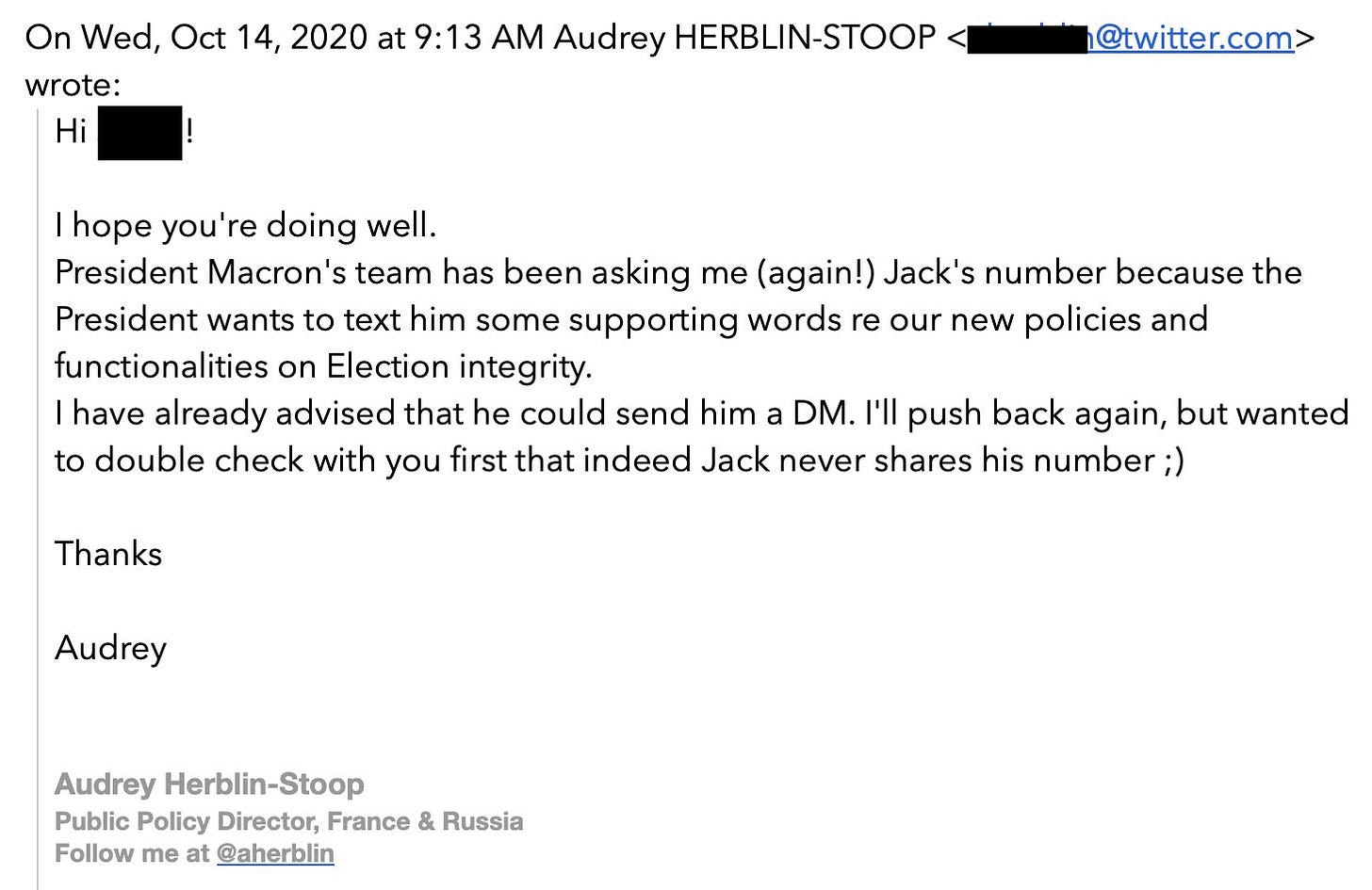

In 2020, Macron personally sought Jack Dorsey’s (then Twitter CEO) phone number, supposedly to congratulate him on “election integrity policies” aimed — once again, supposedly — to address misinformation and interference around elections. It’s worth noting that the foundational justification for such policies was the whole Russiagate controversy — a fabrication since thoroughly debunked.

It’s unclear whether Macron ever did personally get in touch with Dorsey — according to his personal office, “Jack doesn’t have a phone number” — but the episode highlights President Macron’s persistent urge to cultivate direct ties with the CEOs of major digital platforms. He notably granted French citizenship to Evan Spiegel, CEO of Snapchat, and to Pavel Durov, CEO of Telegram — now facing indictment in France on multiple serious charges. Macron has also held several meetings at the Élysée Palace with Mark Zuckerberg, the founder and head of Meta, underlining his sustained effort to establish personal influence over the leaders of global tech companies.

It is reasonable to surmise that Macron’s outreach to Dorsey went beyond a simple gesture of congratulations, but was aimed at personally swaying the policies of US platforms in France — an intervention with potentially far-reaching global ramifications, including for US users themselves. Indeed, Macron’s request coincided with the launch of a lawsuit by four French NGOs against Twitter, raising suspicions of coordinated pressure. The internal communications made available to us by X reveal a deliberate pattern of strategic litigation designed not merely to push content moderation beyond existing legal requirements, but also to shape public opinion and steer legislative developments.

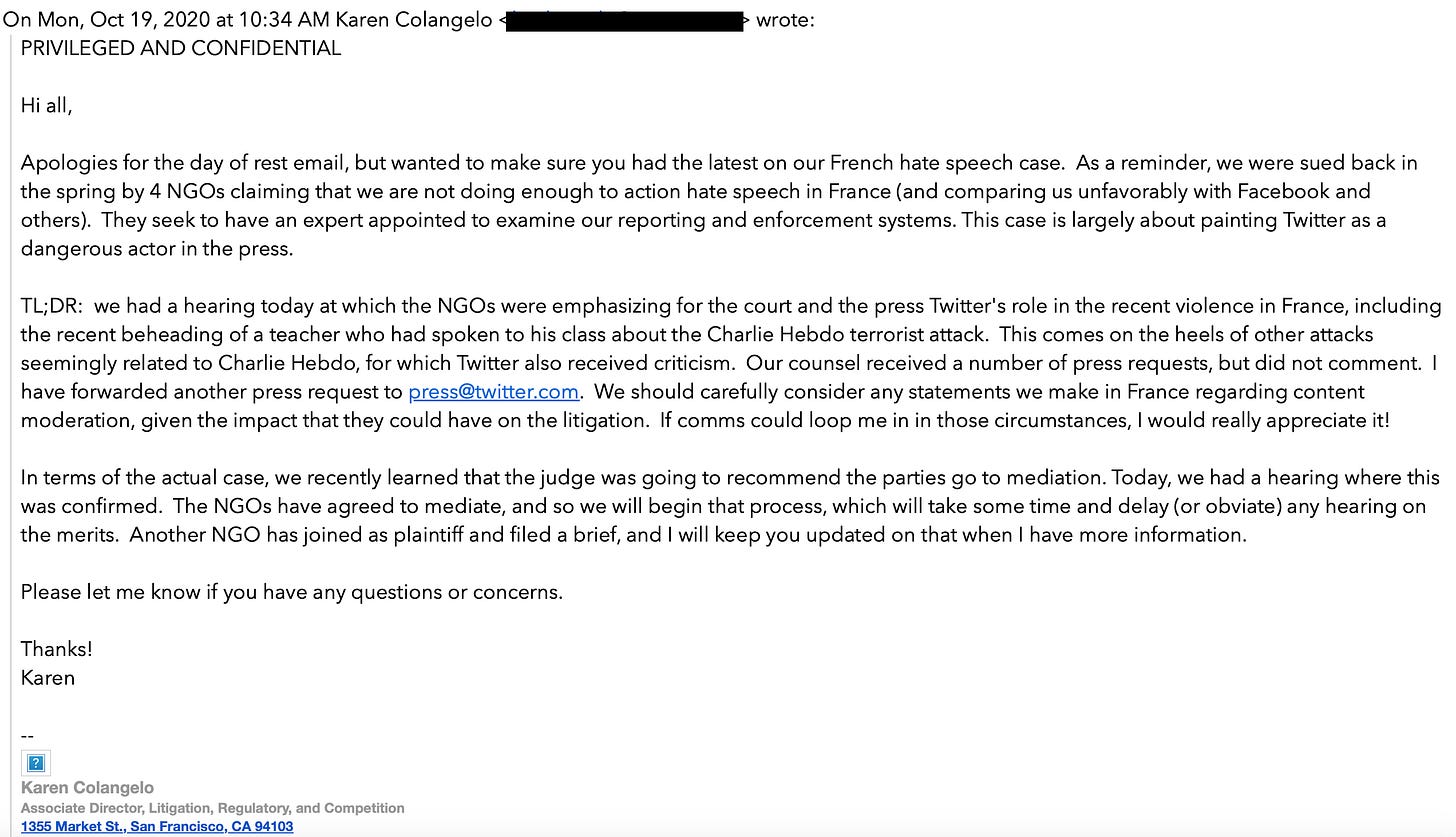

On October 19, 2020, Karen Colangelo, Associate Director of Litigation, Regulatory, and Competition at Twitter, wrote:

We were sued back in the spring by four NGOs claiming that we are not doing enough to address hate speech in France (and comparing us unfavorably with Facebook and others). They seek to have an expert appointed to examine our reporting and enforcement systems. This case is largely about painting Twitter as a dangerous actor in the press.

Colangelo was referring to a suit filed against Twitter by the NGOs SOS Racisme, SOS Homophobie, the Union of Jewish Students of France (UEJF) and J’accuse, claiming that Twitter failed to remove hate speech in a timely manner.

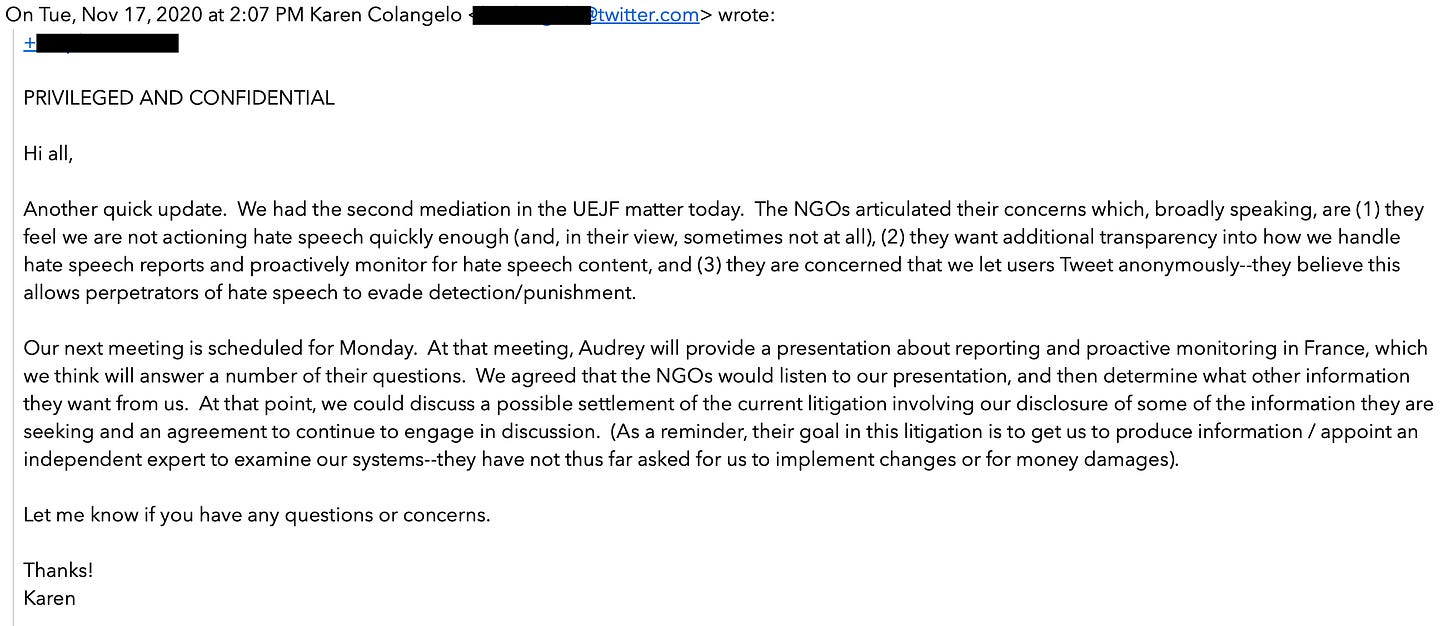

Following a mediation session on November 7, 2020, Colangelo updated her colleagues:

We had the second mediation in the UEJF matter today. The NGOs articulated their concerns, which, broadly speaking, are (1) they feel we are not actioning hate speech quickly enough (and, in their view, sometimes not at all), (2) they want additional transparency into how we handle hate speech reports and proactively monitor for hate speech content, and (3) they are concerned that we let users Tweet anonymously — they believe this allows perpetrators of hate speech to evade detection/punishment.

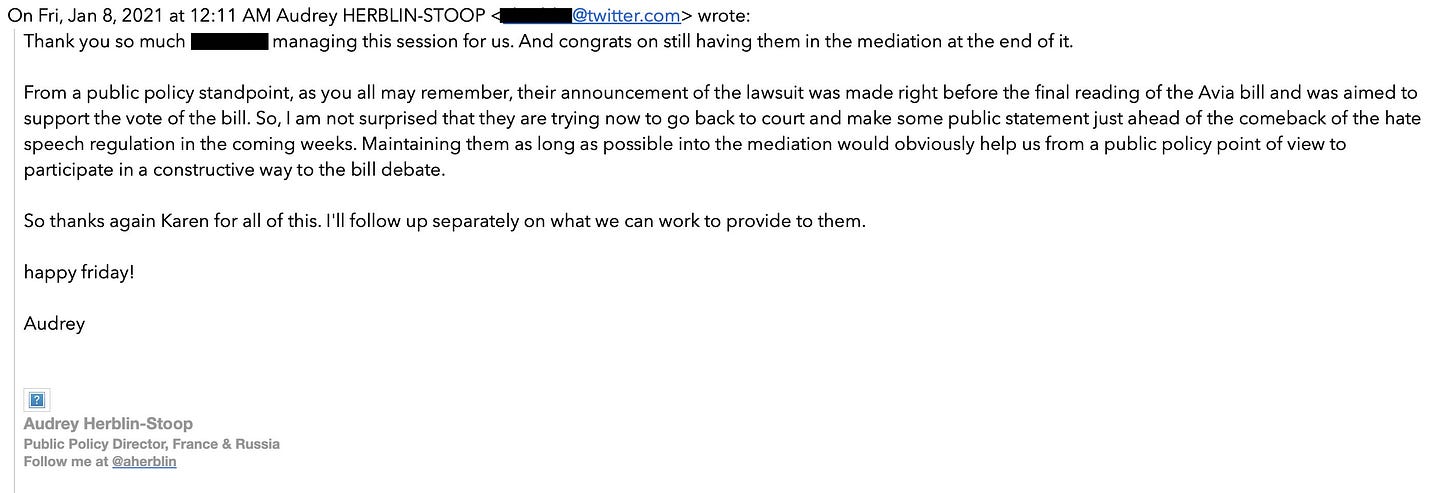

The timing of the lawsuit was not coincidental, as Audrey Herblin-Stoop, Twitter’s Public Policy Director for France and Russia, noted:

From a public policy standpoint, as you all may remember, their announcement of the lawsuit was made right before the final reading of the Avia bill [a law intended to combat online hate speech and illegal content] and was aimed to support the vote of the bill.

This alignment strongly suggests that the litigation was not simply a spontaneous response to online abuse, but part of a broader, coordinated effort in which politically connected NGOs acted in concert with government and legislative actors to generate public pressure and strengthen the case for expanded censorship powers.

It should be noted that under French law the state is barred from imposing preemptive censorship — what in Twitter’s internal communications is referred to as “proactive monitoring”. But, as we explain in our report, state-funded NGOs have long played the role of enforcers, acting through lawsuits, public pressure and strategic litigation to coerce platforms into moderation practices that exceed their legal obligations.

Starting in the early 2010s, these groups initiated a string of legal actions against Twitter over allegedly hateful content. Their lawsuits — targeting antisemitic hashtags, Holocaust denial or homophobic abuse — leveraged the 2004 Law for Confidence in the Digital Economy (LCEN), even though the law does not oblige platforms to proactively moderate content.

In the end, the French judiciary formally dismissed most of the NGOs’ requests in the 2020 trial, such as account suspensions and interference in the platform’s moderation, but nonetheless compelled Twitter to disclose moderation data to civil society groups — rather than to the public or prosecutors. In doing so, they effectively allowed NGOs without standing to gain insider access to Twitter’s internal processes. Internal Twitter communications confirm that NGO litigation was less about strict legal enforcement than about pushing the company into more aggressive, preemptive censorship.

By 2023, the Court of Cassation confirmed that Twitter’s disclosures were inadequate, reinforcing the precedent that platforms could be legally compelled to exceed their statutory obligations. This approach contradicted the international “country-of-origin” principle, which holds that digital content must comply with the laws of the country where it is produced, not where it is consumed. The Trump administration and the US Senate Judiciary Committee are thus correct in asserting that European laws — whether national or EU-wide, such as the Digital Services Act (DSA) — potentially enable the censorship of American citizens.

The litigation surrounding April Benayoum, runner-up in the 2020 Miss France pageant, exemplifies the trend. Subjected to a barrage of antisemitic tweets, Benayoum sued Twitter for failing to act quickly. While courts dismissed most of her claims and acknowledged that Twitter France had no operational control over moderation (which was managed by Twitter International in Ireland), they still ordered disclosures of data relating to reports made to French authorities. The case ultimately ended in a confidential settlement, demonstrating once more how legal action could pressure platforms into concessions.

The French Twitter Files reveal more than a series of isolated lawsuits. They expose a coordinated system involving the presidency, politically connected NGOs and the judiciary — all working to pressure Twitter into censorship practices that go beyond what French law requires.

The implications extend well beyond France. Today, the American complex is being stripped of government funding and authority (though many private initiatives remain active). Yet the censorship-industrial complex continues to operate globally and maintains enormous influence in Europe — particularly in and via France. Indeed, even though France has long presented itself as the cradle of modern democratic ideals, born of the Revolution of 1789 and enshrined in the motto “Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité”, the reality is that few states in the West hold as much sway on free speech as France.

In fact, as we reveal in our report, one might say that France invented the modern censorship-industrial complex. Understanding its origins and mechanisms is crucial, not only because it represents a formidable blueprint for narrative control in the digital age, but also because its influence extends far beyond France’s borders — potentially reaching deep into the US as well.

Historical Foundations: the Birth of a System

From royal censors to revolutionary tribunals, Napoleonic decrees to Vichy oppression, France’s history has long been defined by the tug-of-war between censorship and free speech. A pivotal moment came in 1881, during the Third Republic (1870-1940), with the adoption of the Press Freedom Law. This landmark legislation enshrined protections for free expression by abolishing prior censorship while at the same time defining defamation and insult as criminal offences punishable by fines. Though amended many times, the law remains in force today — albeit progressively weakened in step with the rise of the post-war censorship-industrial complex.

A crucial step in this direction was the passing of the 1972 Pleven Law. Ostensibly aimed at combating racism by criminalising incitement to hatred, defamation or insults based on race, ethnicity or religion, its true revolution lay in procedural innovation. The law shattered a core principle of the foundational 1881 Press Freedom Law: that only the directly aggrieved individual, not the state, could initiate prosecutions for speech offences. Instead, it empowered two state-accredited, partially state-funded NGOs — LICRA (International League against Antisemitism and Racism) and MRAP (Movement Against Racism and for Friendship Between Peoples) — to act as “private prosecutors” with the power to initiate criminal indictments as third parties. This created a potent weapon: NGOs, often ideologically driven and well-resourced, could launch costly, reputation-destroying lawsuits against critics or dissenting voices. This de jure privatisation and de facto weaponisation of the indictment process generated a powerful chilling effect, sharply limiting expression in the mainstream media.

The Pleven Law was less about transposing UN anti-racism conventions (which focused on discriminatory actions, not speech) and more a direct response to rising political tensions — especially mounting opposition to mass immigration, particularly from the French Communist Party. The law provided a tool to delegitimise such discourse. The claim of suppressing racist ideology served as a convenient cover for suppressing criticism of government immigration policies.

The Pleven Law opened Pandora’s box. The 1980s witnessed an explosion of NGOs, often presenting noble causes (anti-racism, feminism, etc.) but frequently acting as proxies for political parties or interest groups. These groups relentlessly lobbied for accreditation and expanded powers to initiate indictments in new domains (sexual orientation, historical memory, etc.), turning lawfare into a core political strategy.

The 1990 Gayssot Law marked a dangerous escalation, criminalising Holocaust denial and revisionism and imposing harsher penalties for Pleven offences. Its primary purpose, however, wasn’t historical integrity but political warfare: namely to demonise Jean-Marie Le Pen’s rising National Front (FN), which Socialist President François Mitterrand had covertly boosted to split the right, only to see it gain nearly 15% of the vote in 1988. This tactic increased voter abstention, preserving establishment power while crippling democratic engagement.

Similarly, the 2001 Taubira Law recognised slavery as a crime against humanity and authorised NGOs representing descendants to initiate prosecutions, while its sponsor, Christiane Taubira, publicly discouraged discussion of the Arab Muslim slave trade to avoid offending certain communities. In short, over time, France developed a disturbing pattern of selectively criminalising the past.

This 1972 model — state-sanctioned NGOs wielding prosecutorial power over defined categories of speech — established the foundational pillar of the French censorship-industrial complex decades before social media even existed.

Institutional Machinery: the State’s Web of Control

France’s censorship complex isn’t a shadowy “deep state”; it is the state — a permanent, centralised apparatus distinct from transient governments. Its control over information flows is achieved through a multi-layered, often oblique, system of subsidies, ownership, regulation, surveillance and legal frameworks.

Starting in 1945, radio — and later television — broadcasting was established as a state monopoly. Despite the liberalisation of the broadcast media in the 1980s through licensing by a regulator, today known as ARCOM, the French public broadcasting system remains a powerful media leviathan: comprising France Télévisions (10 national TV channels) and Radio France (8 national and 44 local stations), it represents the largest media group in France, operating on a €4 billion annual budget. This dwarfs that of leading private networks. Moreover, the latter are also subject to strict control by ARCOM, which meticulously tracks political labels and speaking times of pundits, often applying double standards that disadvantage conservatives and populists. During elections, airtime allocation is based on past results, structurally favouring incumbents.

Meanwhile, the printed press survives on a massive infusion of state cash. Direct and indirect subsidies, state advertising and local government PR spending total over €1.8 billion annually — more than one-third of the sector’s €6 billion revenue. Accreditation, granting access to subsidies, tax breaks and distribution is controlled by the Joint Commission for Publications and Press Agencies, chaired by a member of the Conseil d’État (Council of the State), France’s highest administrative court and composed equally of state and industry representatives (the latter chosen from establishment-aligned bodies). This fosters dependency and conformity.

To make matters worse, 80-90% of private mainstream media is controlled by just eight billionaires: Bernard Arnault, Xavier Niel, Vincent Bolloré, Rodolphe Saadé, Daniel Kretinsky, Martin Bouygues, the Dassault family and François Pinault. Among these, only Bolloré has media as a core business. For the others, media ownership is a tool for influence and protection. Crucially, their vast fortunes are deeply intertwined with the state: reliant on government contracts, operating licenses or acquiring privatised assets at discounted prices. It is therefore no exaggeration to say that while French mainstream media are formally free, they remain deeply influenced by owners whose interests are closely aligned with those of the political establishment — and, above all, the state itself.

Furthermore, over the years, the state has shown no qualms about pushing or overstepping the boundaries of the law in controlling the press. While the 1881 law forbids pre-publication censorship, intelligence agencies have a long, documented history of obtaining pre-publication proofs and coercing or bribing journalists. François Mitterrand infamously ran an illegal wiretap operation (1982-86) targeting journalists, artists and politicians. Today, mass surveillance capabilities — often justified by exaggerating terrorist threats — allow metadata tracking of journalist-source communications, despite EU court rulings against bulk collection.

Meanwhile, in recent years, the Pleven Law model has been expanded with the DSA. In July 2025, Minister Aurore Bergé announced a coalition of state-funded NGOs specifically hired to “combat online hate”. This formalises the privatisation of speech policing, directly funded by the state to target disfavoured viewpoints under the banner of fighting “hate speech”.

The judiciary — trained at the elite National Judiciary School (ENM) — is also increasingly politicised. District Attorneys (DAs), who initiate prosecutions, are appointed by the President. Macron has systematically appointed loyalists with minimal courtroom experience but strong political ties to key posts. This enables indirect control over sensitive cases. This was brought into stark relief during the campaign for the 2017 presidential election: despite a relentless PR campaign driven by oligarch-owned mainstream media, Macron was still languishing in third place in the polls by the end of 2016, trailing behind right-wing candidates François Fillon and Marine Le Pen.

His ascent began only after the coordinated efforts of high-ranking civil service and the senior judiciary, which led to Fillon’s indictment in March 2017 — the fastest in France’s judicial history, resulting from an investigation that lasted only a month and a half — for misappropriation of public funds. This pivotal intervention took out of the race the front-runner poised to become the next president and propelled Macron in the polls, culminating in his victory over Marine Le Pen in the second round. Ultimately, Macron’s election was secured through the strategic manoeuvring of the senior civil service, the high judiciary and the oligarchs who all had championed his candidacy. To put in bluntly: it was a coup fomented by the elite.

This intricate web — combining financial leverage, oligarchic alignment, regulatory oversight, surveillance, privatised prosecution and a compliant judiciary — forms the robust institutional backbone of the French censorship-industrial complex.

Digital Expansion: Legislating the Online Panopticon

The internet’s rise has shattered traditional information gatekeeping, triggering panic among Europe’s elites, culminating in the EU’s adoption, in 2022, of the Digital Services Act (DSA) — the most sweeping internet regulation ever implemented in Europe, obliging platforms to rapidly remove content deemed illegal by EU authorities or face fines of up to 6% of their global annual revenue. Marketed as a way to “make the internet safer”, its aim is quite clearly that of secretly controlling the online narrative, by compelling platforms to police online speech according to broad, politically charged definitions of “harm” and “disinformation”.

The DSA forms the bedrock of Europe’s state-backed censorship‑industrial complex, but in many respects France has gone even further, embarking on a relentless legislative and regulatory onslaught aimed at replicating offline control mechanisms online. The early foundation of French online censorship lay in the 2004 Law for Confidence in the Digital Economy (LCEN). Though the law officially represented the transposition into national law of an EU e-commerce directive aimed primarily at ensuring free and fair competition, market access and consumer protection, France went further, adding stringent censorship provisions.

It established the “notice-and-takedown” framework, granting platforms liability immunity only if they removed illegal content upon request and provided user data. Crucially, requests could come not just from courts, but also from state administrative bodies. This created the blueprint for administrative censorship. This was exacerbated in 2009 by the launch of the PHAROS platform, operated by law enforcement, which enables citizens to report content, further automating the takedown demand pipeline.

By 2012, France was already the global leader in censorship requests to Twitter, demanding “prebunking” measures. The predicaments faced by Microsoft and Facebook that same year further highlight how the state obliquely gets his way. Tax raids on the two companies over billing practices were followed by Facebook appointing Laurent Solly, senior advisor to former President Nicolas Sarkozy at the time he was Finance Minister, as its French CEO — revealing a pattern of hiring politically connected insiders to navigate bureaucracy and ensure compliance. The threat of massive fines or tax adjustments remains a powerful lever.

2016 marked an inflection point in the state’s crackdown on online speech. Events like Brexit, Trump’s victory, the Arab Spring and France’s Yellow Vest movement, organised via social media, convinced elites that “information disorders” represented an existential threat to their power. A consensus thus emerged: digital platforms needed to be regulated to curb the rise of populism. This led Macron to launch a legislative onslaught:

The 2018 Law Against Manipulation of Information: despite existing laws criminalising false news, this law mandated that platforms implement “misinformation” detection tools and ensure algorithmic transparency during elections under ARCOM supervision. It was a Trojan horse for platform-level narrative control.

The 2020 Law Against Hate Speech on the Internet: by imposing draconian removal deadlines — giving platforms a stringent 24-hour window to remove content deemed illegal or hateful by authorities or users — it effectively compelled platforms to adopt prebunking and automated censorship. Failure to comply could incur a penalty of up to 4% of a platform’s global revenue, enforced by ARCOM. The Constitutional Council struck it down for violating free speech, but Macron immediately vowed to push its core tenets via the EU during France’s 2022 presidency.

The 2021 Law on Strengthening Republican Principles: it added complex layers requiring platforms to combat “hate speech”, “separatism” and “anti-republican content”. The compliance burden itself acts as coercion towards over-removal and automation.

The 2024 Law on Securing and Regulating the Digital Space (SREN): it is the primary legislation addressing deepfakes and related issues, requiring platforms to promptly remove non-consensual deepfake content and address content involving online harassment or illegal data sharing. Crucially, the SREN law integrated into French law the EU’s Digital Services Act — designating ARCOM as France’s Digital Services Coordinator (DSC), responsible for overseeing DSA compliance — while introducing additional national provisions to enhance “digital safety” and regulation.

Push to ban social media for under-15s: following a fatal stabbing in a school, Macron said he would push for European Union regulation to ban social media for children under the age of 15 — or go at it alone. This amounts to a thinly veiled tactic to compel the identification of all users through the EU’s biometric ID card system — a way to track the online activity of each and every citizen.

A special mention goes to VIGINUM, the counter-disinformation agency launched by Macron in July 2021. Its official mandate is to detect foreign “information manipulation” threatening national interests via open-source monitoring of large platforms. However, its actions and leadership — Lt. Col. Marc-Antoine Brillant, a counter-insurgency specialist, and Hervé Letoqueux, a judicial custom officer with experience in counter-terrorism and cybersecurity — suggest a broader role. For example, it has been suggested that it was implicated in the contested cancellation of Romania’s 2024 presidential first round, alleging an unproven Russian-backed TikTok campaign for sovereigntist candidate Călin Georgescu. VIGINUM reports often lack concrete attribution but fuel narratives used for domestic and foreign information operations under the guise of “cognitive security”.

This digital expansion represents a systematic effort to build an online panopticon: delegating censorship to NGOs, eliminating anonymity via digital IDs and enforcing narrative conformity through algorithmic control and the constant threat of crushing fines. The goal, one might say, is full-spectrum online narrative control under the guise of protecting citizens from domestic and external threats — an extension of the national security state into the digital realm.

Tightening the Noose Around Tech Firms and the Opposition

Over the past year, the censorship-industrial complex has escalated its war on platforms and opposition figures, using the full weight of lawfare and judicial intimidation.

In August 2024, Telegram’s founder, Pavel Durov, was arrested in Paris, held for four days, and indicted on a staggering list of charges, including: complicity in organised crime, drug trafficking, fraud and child sexual abuse material distribution; refusal to provide data for lawful interception; criminal conspiracy; money laundering; and facilitating terrorism. The move reeks of political retaliation.

Durov consistently refused to install backdoors in Telegram, used by over 1 billion, mainly non-Western users around the world. Crucially, Macron, his party and ministers heavily used Telegram (2015-2022) believing it secure. Its client-server architecture (not true end-to-end encryption) means Telegram potentially holds years of sensitive French government communications. In spring 2025, Durov allegedly met with Nicolas Lerner, the director of the DGSE, France’s foreign intelligence service. According to Durov, Lerner urged him to suppress conservative voices on Telegram in the wake of Romania’s presidential election’s reboot. Both the French Ministry of foreign affairs and the DGSE denied Durov’s claims.

Meanwhile, in July 2025, Paris DA Laure Beccuau (also prosecuting Durov) opened a criminal investigation into X and its management for interference with an IT system operation, fraudulent data extraction and foreign interference. These are significant cybercrime offences, carrying penalties under the criminal code of up to ten years in prison and a fine of €300,000. Beccuau stated that her decision to prosecute was grounded on complaints from French researchers and evidence provided by various public institutions — though to this day these sources have not been revealed. It seems clear that the case aims to force X into algorithmic compliance with state-approved narratives.

Recent years have also seen a rise in asymmetrical prosecutions and convictions targeting political figures. The latest example is the case of Marine Le Pen, who earlier this year was found guilty of embezzling EU funds and sentenced to four years in prison, of which two were suspended, and a five-year ban on holding public office, a penalty the trial court ordered to take effect immediately despite Le Pen’s appeal. This eviscerates the presumption of innocence and allows judges to effectively bar leading candidates.

These cases demonstrate the evolution of the censorship-industrial complex: when censorship and narrative control falter, the system deploys the blunt instruments of criminal prosecution and judicial elimination against its most critics, both human and corporate.

An Illegitimate Elite’s Last Stand?

The sprawling French censorship-industrial complex is not an accident; it’s the desperate reflex of an elite facing an existential crisis. Failures on multiple fronts — economic stagnation, the disastrous Ukraine policy draining billions, the erosion of living standards — have shattered their legitimacy. The democratising power of the internet has exposed elite disconnect and fostered populist challenges. The complex is the tool to rebuild control: extending “cognitive security” as a national security imperative, regulating the digital public square as tightly as the state once regulated broadcast airwaves.

However, its foundations are cracking. Public trust is at historic lows. Technology evolves faster than regulation. Citizens migrate to encrypted spaces. The elite, trapped in obsolete globalist dogma and Cold War top-down control mentalities, responds with escalating coercion: more laws, more fines, more prosecutions, more judicial overreach. Their technocratic arrogance — believing they alone can discern truth and must “protect” citizens from wrongthink — fuels this authoritarian turn.

The outcome is uncertain. Bureaucracies seek self-preservation, and entrenched elites cling fiercely to their privileges. Yet, our report suggests these obsolete ruling elites may ultimately be overwhelmed by the very technological and social forces they seek to suppress. France may have built the most sophisticated censorship machine in the West, but its victory over the digital public square is far from assured.

Read the full report here.

Thanks for reading. Putting out high-quality journalism requires constant research, most of which goes unpaid, so if you appreciate my writing please consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you haven’t already. Aside from a fuzzy feeling inside of you, you’ll get access to exclusive articles and commentary.

Thomas Fazi

Website: thomasfazi.net

Twitter: @battleforeurope

Latest book: The Covid Consensus: The Global Assault on Democracy and the Poor—A Critique from the Left (co-authored with Toby Green)

so essentially what you are suggesting is the elites are threatened, so they are fully on board with the censorship security complex.... that sounds valid.. it seems to me the amount of censorship in many of the western countries - not just france - is ramping up and heading off the charts... i attribute much of this to the intel agencies who can fictitiously claim all sorts of nonsense without having to prove any of it.. case in point - russiagate from 2018 which is shown to be a made up fiction...

so my question is on DGSE, France’s foreign intelligence service - how does this differ any from 5 eyes, or 6 eyes if we include mossad in the intel agency conglomerate?? it seems to me these intel agencies are driving much of the policy and the policy is to clamp down and suppress alternative viewpoints, or any alternative ideology which threatens the status quo... therefore we always have to be at war and at odds with russia and china, no matter if it is just as possible to get along... the intel agencies seem to work in collaboration with the military industrial complex, both protecting each other while building up their fortunes.. the politicians are only too happy to comply with this ongoing agenda which doesn't serve the people of the planet one bit..

maybe AI will help to make it all worse.. i can't see it making any of it better..

thanks for your posts!

Reporters without borders (but with gov funding) another French NGO, has this to say about FR and US press freedom:

US #57 out of 180.

'After a century of gradual expansion of press rights in the United States, the country is experiencing its first significant and prolonged decline in press freedom in modern history, and Donald Trump’s return to the presidency is greatly exacerbating the situation...

While the media in the United States generally operate free from government interference, media ownership is highly concentrated, and many of the companies buying American media outlets appear to prioritize profits over public interest journalism'

https://rsf.org/en/country/united-states

Etc etc

FR #25 out of 180. (Apparently press freedom in FR is twice as delicieux as its frère in the US).

'While the legal and regulatory framework is favourable to press freedom, the mechanisms aimed at combatting conflicts of interest in the media and protecting the confidentiality of sources are insufficient, inadequate, and outdated. The public broadcast media are undermined by the lack of sustainable funding caused by the elimination of the TV licence fee. Despite the adoption of a new method of maintaining order during demonstrations, more respectful of journalists’ rights, reporters continue to be subjected to police violence in addition to physical attacks by demonstrators'

https://rsf.org/en/country/france

That 'conflict of interest' they mention no doubt is about the new(er) competion i.e. right wing media growing fast in FR (why would that be?).

But, clearly, to this FR gov funded NGO the ideal sitaution is as follows:

We speak, you listen.

Say thanks.