What is the Russian-Iranian strategic partnership agreement really about?

The agreement represents an important channel to circumvent the sanctions affecting both countries, further undermining the global dominance of the US dollar

Guest post by Roberto Iannuzzi, originally published in Italian on his Substack.

On January 17, just three days before Trump’s inauguration, Russia and Iran signed a long-awaited “Comprehensive Strategic Partnership Agreement” after lengthy negotiations. The timing didn’t go unnoticed by Western commentators, who highlighted Iran’s assistance to Russia in the Ukrainian theater of war, particularly through the supply of Iranian-made drones. They also pointed out that the new US president has signalled a tough stance toward Iran while promising to end the conflict in Ukraine — though it is unclear how, and Trump himself has not ruled out tightening sanctions against Moscow.

For his part, Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov denied any connection between the signing of the agreement and Trump’s inauguration. Nevertheless, the event undoubtedly marked a further strengthening of ties between two countries that are both subject to harsh Western sanctions and have strained relations with the West.

The treaty was signed at the Kremlin during a visit by Iranian president Masoud Pezeshkian, who led a large delegation. This long-awaited move comes at a time when the Iranians “are frightened by the Trump administration, they are frightened by Israel, they are frightened by the collapse of Assad, the collapse of Hezbollah”, as noted by Nikita Smagin, an analyst who previously worked for Russian state media in Tehran before the Ukrainian conflict.

Observers are divided on the significance of the agreement. Some have described it as a “historic turning point”, while others have downplayed it as vague and falling short of expectations.

No intention to escalate tensions with the West

Nematollah Izadi, Iran’s last ambassador to the Soviet Union, described the pact as one aimed at building mutual trust. According to him, Tehran seeks to reassure Moscow that it will not betray this promising bilateral relationship, even as it attempts to ease tensions with the West.

Pezeshkian, a reformist, won the presidential election on a platform focused on improving Iran’s struggling economy. This can only be achieved by lifting the crippling sanctions that suffocate the Iranian economy, which in turn requires a negotiated resolution to the nuclear issue. Iran’s nuclear program has now reached a level of development that makes it a “latent” nuclear power. Iranian leaders are satisfied with this status and hope to reopen dialogue with the West.

Pezeshkian, in agreement with supreme leader Ali Khamenei, aims not only to secure the removal of sanctions but also to prevent a potential Israeli-American military strike on Iran’s nuclear facilities, which could plunge the entire region into catastrophic war. The return of Donald Trump to the White House complicates this effort. Trump unilaterally withdrew from the nuclear deal negotiated by his predecessor, Obama, and ordered the assassination of general Qassem Soleimani, a national hero in Iran. Despite this, Iran appears determined to try.

Encouraging signals have also come from the White House, where the newly inaugurated president seems intent on entrusting negotiations with Iran to Steve Witkoff, the special envoy who brokered a ceasefire in Gaza with Netanyahu.

For its part, Moscow has been careful to ensure that the partnership agreement with Iran is not interpreted as the formation of an anti-Western or anti-Israeli alliance. This is likely why the signing of the agreement was delayed for so long. During the BRICS summit last October in Kazan, the deal seemed ready for ratification, but Russian president Vladimir Putin asked Pezeshkian to make another visit to Moscow specifically to sign the document. This request, ostensibly for protocol reasons, was likely motivated by Russia’s desire to wait for tensions in the Middle East to ease, as the war between Israel and Hezbollah in Lebanon was raging at the time, and relations between Tehran and Tel Aviv were extremely tense.

A long path to rapprochement

The idea of a strategic partnership agreement, replacing the previous treaty signed by the two countries in 2001, first emerged in 2020. After failing to improve relations with the West, then-Iranian president Hassan Rouhani decided to look to non-Western countries. The first strategic partnership agreement was signed with China in March 2021, followed by agreements with Venezuela and Syria. Negotiations with Russia intensified after the outbreak of the Ukrainian conflict. According to diplomatic sources, finalising the text required between 20 and 30 negotiation sessions over five years.

In the meantime, relations between the two countries have strengthened economically and militarily due to the Ukrainian crisis and the isolation both have faced as a result of Western ostracism. The text of the partnership agreement does not contain any particularly groundbreaking provisions but rather summarises and formalises the strengthening of relations over the past three years and the resulting agreements in various areas of cooperation.

The new treaty contains 47 articles covering a wide range of areas: economic and trade cooperation, technological collaboration, the peaceful use of nuclear energy, counterterrorism, regional cooperation, and more. Unlike agreements Russia has signed with North Korea and Belarus, the document does not include a “mutual defence” clause. This is likely because Russia does not want to risk going to war directly with Israel or the US to defend Iran.

On the other hand, Iranian leaders also remain cautious toward Moscow, recalling the territorial concessions Iran had to make to the Russian Empire in the first half of the 19th century and Russia’s role as a colonial power in Iran, competing with the British Empire in the early 20th century. More recently, tensions arose between Tehran and Moscow following the unexpected and sudden collapse of the regime of Syrian president Bashar al-Assad, an important ally for both in the Middle East. However, these disagreements have not disrupted the partnership, even though the strategic interests of the two countries do not always align.

Reserve on military cooperation

The agreement does, however, provide for the exchange of security and intelligence information (Article 4), adding that the level of cooperation in this area will be specified in “separate agreements”. Article 5, which deals with military relations, covers a broad scope but is also somewhat vague: “The Contracting Parties shall consult and cooperate in countering common military and security threats of a bilateral and regional nature”.

Again, the text specifies that the development of military cooperation between relevant bodies will be implemented through separate agreements. This suggests that the treaty maintains a certain level of secrecy regarding military and intelligence collaboration.

Regarding the sanctions both countries face, the document explicitly states that Moscow and Tehran will collaborate to counter “the application of unilateral coercive measures” and “guarantee the non-application” of such measures “aimed directly or indirectly against either Contracting Party”.

The Caucasus issue

An important section of the agreement is dedicated to the Caucasus, where a significant part of the future of the partnership between the two countries will be decided. Article 12, described as “of fundamental importance” by some Russian experts on the region, commits the two signatories to strengthening peace and security in this area (as well as in Central Asia, the South Caucasus and the Middle East) and to “cooperate to prevent interference” and the “destabilizing presence of the third states” in the region. It is reasonable to assume that these countries include the US, the UK, Israel, EU member states and possibly Turkey.

In this regard, it is worth noting that Armenian prime minister Nikol Pashinyan’s “flirtation” with the US and the EU, as well as Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev’s close ties with Turkey and Israel, have put Yerevan and Baku at odds with Moscow and Tehran, respectively.

Article 14 commits the parties to promoting trade expansion between Iran and the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), of which Russia is a founding member. This year will see the implementation of a free trade agreement between Iran and the EAEU, which will reduce tariffs on 90 percent of traded goods. In this context, the shared border between Iran and Armenia, an EAEU member, in the mountainous province of Syunik is particularly important.

Azerbaijan claims the so-called “Zangezur Corridor” in this region, which would connect it to its exclave of Nakhchivan. This ambition aims to create what Tehran calls the “NATO Turanic Corridor”, linking Central Asian republics and their energy resources to Turkey (a NATO member) via Azerbaijan and Nakhchivan.

The realisation of this corridor would allow NATO access to the Caspian Sea. Thus, the outcome of this dispute will be crucial for the future of Russia-Iran relations.

The energy and trade challenge

Article 13 focuses exclusively on the Caspian region, which is important for Moscow and Tehran not only in terms of security but also energy, transportation and trade cooperation. It reflects Iran's aspiration to become an international gas hub, a vision that Russian leaders had previously proposed to Turkey when relations between the two countries were friendlier.

Moscow intends to redirect part of its energy export plans from China (with which pricing disputes persist) toward Iran, in a sort of “southward pivot” that would represent a third outlet for Russian energy resources, alongside Europe and China. Through a pipeline that would cross Azerbaijan, Russia would initially export just 2 billion cubic meters of gas annually to Iran, eventually reaching 55 billion — the same capacity as the now-defunct Nord Stream 1 pipeline to Germany.

Russian technology and investment could also unlock Iran’s vast gas reserves, freeing Tehran from the energy crisis that paradoxically stifles it due to sanctions and lack of investment, and enabling the two countries to create a gas cartel capable of managing global prices and supplying nearby India.

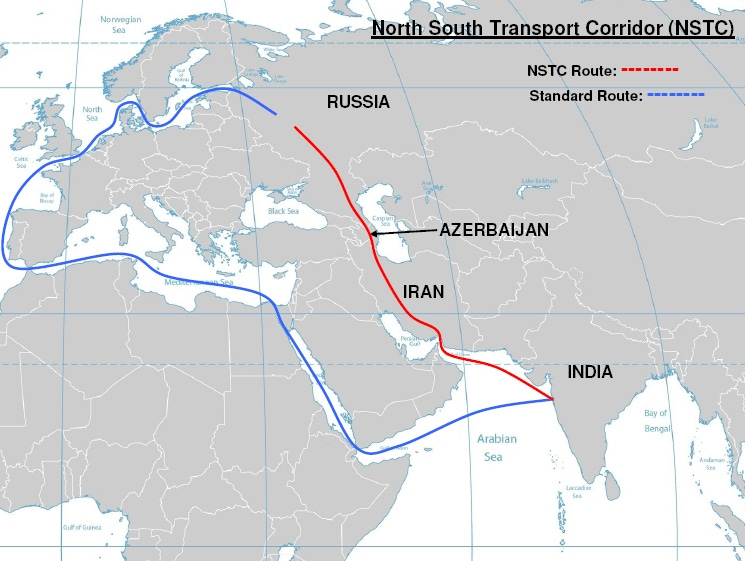

The Caspian and Caucasus are essential for the realisation of the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC), a logistics corridor that allows Moscow to export its goods to Asia and Africa via Iran, bypassing the Baltic, Black Sea and Suez Canal.

However, the value of trade between Russia and Iran remains modest, hovering between $4 and $5 billion. The Iranian economy continues to suffer from a lack of investment and decades of Western sanctions. The development of the INSTC should provide Moscow and Tehran with an important channel to circumvent the sanctions affecting both countries, which are also integrating their national payment systems. In 2024, transactions in Russian rubles and Iranian rials accounted for over 95 percent of bilateral trade.

The potential for economic cooperation between Russia and Iran is therefore promising, provided the two countries can devise joint systems to evade sanctions. Militarily, however, Moscow and Tehran are not fully aligned, leaving Iran particularly exposed to the risk of an Israeli-American military intervention should the upcoming negotiations with the newly inaugurated Trump administration fail.

Thanks for reading. Putting out high-quality journalism requires constant research, most of which goes unpaid, so if you appreciate my writing please consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you haven’t already. Aside from a fuzzy feeling inside of you, you’ll get access to exclusive articles and commentary.

Thomas Fazi

Website: thomasfazi.net

Twitter: @battleforeurope

Latest book: The Covid Consensus: The Global Assault on Democracy and the Poor—A Critique from the Left (co-authored with Toby Green)

If NATO expansion into Ukraine has achieved anything positive perhaps this mutual support between Iran and Russia is the positive. When any nation or organization gets too much power, it does not bode well for the entire planet. Balance of power between the big bullies is better for all of us.

Excellent summary. Thank you.