Europe’s future depends on dismantling the EU — part one

A comprehensive critique of the EU’s supranational model of integration, analysing its structural, economic and geopolitical shortcomings

This is part one of a study I’ve been working on for a while. It provides a comprehensive critique of the EU’s supranational model of integration, analysing its structural, economic and geopolitical shortcomings. It highlights the way in which EU and the single currency, far from making Europe stronger, more competitive and more resilient, have paved the way for economic crisis and stagnation, worsened economic disparities, and contributed to loss of competitiveness, geopolitical marginalisation and democratic decay.

Crucially, the study argues that failure of the EU project isn’t rooted in a lack of integration — and definitely cannot be solved by resorting to “more Europe” — but rather lies in supranational integration itself. It concludes that the EU’s structural deficiencies are irreparable within the confines of its existing model and questions the viability of supranationalism as a viable governance approach in a multipolar and state-driven global order.

The next parts will be published in the following days, and will be available only to paid subscribers.

Key points

Supranationalism as a failed paradigm:

The EU’s supranational model was premised on the idea that that “pooling” national sovereignty into a supranational institution would empower member states individually and collectively. But the assumption that deeper integration would inherently produce better economic and social outcomes has proven false. On the contrary, it has hampered growth and economic dynamism. This is due to the intrinsic economic and (geo)political shortcomings of supranationalism.

Failure of economic integration:

EU integration has failed to deliver promised economic benefits.

The EU has lagged behind comparable economies like the United States, particularly in terms of innovation, productivity and economic dynamism. The study identifies key structural constraints imposed by the supranational model as key reasons for this stagnation.

This is largely due to the structural deficiencies of the single currency, which has eroded individual nations’ capacity to respond flexibly to domestic and external challenges based on their economic and political needs, as well as their citizens’ democratic aspirations, while failing to adequately compensate for this at the European level.

Anti-industrial policy bias:

The EU’s supranational paradigm is fundamentally misaligned with the current global order, which is increasingly shaped by state-led industrial strategies and geopolitical competition. The EU’s neoliberal framework and stringent state aid rules discourage state-led industrial policies essential for fostering innovation and competitiveness. This bias, codified in EU treaties and regulatory frameworks, leaves Europe ill-prepared to compete with countries like the US and China, which actively engage in strategic industrial policies.

Governance issues:

The EU’s complex governance, marked by fragmented and bureaucratic decision-making, further hampers its ability to respond to crises or implement coherent policies. Attempts to centralise investment and industrial policy often result in inefficiency, further undermining the EU’s capacity to act as a unified entity.

Technocracy leads to bad policy outcomes:

The EU’s supranational framework, which prioritises technocratic decision-making over democratic representation, reduces national democratic control, concentrating power in unaccountable institutions like the European Central Bank and the European Commission. This has led to policies that prioritise elite and oligarchic interests over those of citizens.

The EU’s alignment with US policies, particularly on Ukraine and China, has exacerbated its energy crisis and industrial decline. High energy costs and ineffective tariffs have further weakened industrial competitiveness. This has exacerbated the EU’s economic and geopolitical marginalisation.

Policy recommendations:

The EU’s failures are inherent to the supranational paradigm itself. Attempts to address these shortcomings within the current framework often exacerbate the problems.

The study suggests going beyond the current supranational model and empowering nation-states with flexibility for tailored economic and industrial policies, enabling strategic public investment and reducing reliance on centralised, bureaucratic decision-making.

It also recommends considering alternative, flexible cooperation models that preserve national sovereignty while fostering economic and political collaboration.

Introduction

For the past three decades or more, a dominant narrative has shaped the European discourse: in an increasingly globalised and interconnected world, individual nations have become progressively constrained in their economic autonomy and have lost the capacity to independently determine their economic trajectory. This is attributed to their weakness relative to powerful external forces — both private entities such as international finance and multinational corporations, as well as foreign superpowers, particularly China. According to this view, the very concept of national sovereignty has become increasingly obsolete in today’s world.

The solution, according to this narrative, was for European nations to “pool” their sovereignty and transfer it to a supranational institutional large and powerful enough to have its voice heard in the international arena: the European Union (EU). The argument maintained that only at this supranational, continental level could individual states achieve sufficient collective power to implement effective economic policies in relation to these global forces. In other words, relinquishing certain elements of national sovereignty — already deemed practically diminished — would enable countries to reclaim a form of “real” sovereignty through collective strength. This forms the core of the supranationalist pro-EU argument.

Central to this argument is the belief that deeper integration leads to greater benefits. Limited forms of integration were thus used to justify subsequent steps in the integration process. The creation of the Single Market, for example, was justified on the grounds that it would enhance intra-European trade; this, in turn, led to calls for monetary union as a way of improving the functioning the Single Market — as well as spurring economic growth, employment and stability.

This narrative has been a cornerstone of the economic justification for the European Union project, underpinning the systematic transfer of sovereign powers from national governments to the EU institutions in Brussels and Frankfurt. While other justifications for European integration exist, this economic rationale has been particularly influential in shaping public and political support for the EU.

Its persuasiveness stems from its strong appeal to common sense: the idea that in a challenging global environment collective action provides greater strength — economically and politically — resonates as intuitive and pragmatic. However, this argument contains a fundamental flaw: if it were valid, the countries that went on to join the Single Market, and then the EU, would have demonstrated improved economic performance relative to their pre-EU trend; member states that embraced deeper integration — such as those that adopted the euro — would have consistently outperformed those that did not; and the EU would have rivalled or outperformed comparable economies. Empirical evidence, however, shows that none of these outcome have materialised.

On the contrary, European integration — through its successive phases, including the Single Market, the post-Maastricht European Union and the introduction of the single currency — has largely failed to enhance the economic performance of member states by most metrics, both collectively and, for many countries, individually, relative to their pre-integration trendlines. Several eurozone countries have experienced weaker economic outcomes compared to EU member states that chose to remain outside the monetary union, while the EU as a whole has consistently underperformed relative to the United States, a comparable economic entity.

The standard response from an integrationist perspective is that the issue stems from EU member states not transferring sufficient authority to the Union’s supranational institutions. In this view, the problem is consistently framed as a lack of integration, with the solution invariably being “more Europe”. The latest example is Mario Draghi, who in a recent speech, after decrying Europe’s slide into geopolitical irrelevance, concluded that “the European Union will have to move towards new forms of integration” — meaning deeper political, fiscal, military and technological centralisation. In other words, Europe’s problems, in his view, can only be solved by transferring still more authority to Brussels and further sidelining national governments and parliaments.

However, this argument is refuted by historical evidence — as well as basic logic. As argued in this study, the EU’s problems don’t lie in a lack of integration, but in supranational integration itself.

This is why the steady increase in the power and scope of the EU’s supranational institutions, such as the European Central Bank (ECB) and European Commission, has not delivered better outcomes, but has only tended to make things worse. The study argues that, ultimately, the problems created by the flawed institutional framework of the EU are unresolvable within the framework of the EU itself, from both a political as well as economic standpoint.

Such a radical critique of the European Union may appear unreasonable or politically inconvenient in a context in which the debate about the EU, and even the single currency, would appear to have been settled once and for all: contrary to just a few years ago, there is virtually no major political force in Europe today that challenges the EU’s viability or advocates for member states to exit the eurozone. This partly reflects a heightened awareness of the complexities and costs of dismantling, or disentangling from, the Union — but also a failure of political imagination. As a result, even so-called “populist” parties now argue for reforming these institutions from within.

Such attempts should be welcomed, and may even achieve some limited results. However, in light of the extensive damage already caused by the EU/euro, not just in economic terms — which is largely the focus of this study — but in (geo)political and democratic-representative terms as well, we cannot shy away from challenging the consensus and asking tough questions: is there any evidence that supranationalism is a viable response to today’s global challenges? What realistic prospects are there for fundamentally reforming the EU? And, if not, what does this mean for the future of Europe?

The study is structured as follows:

1. The economic performance of the EU so far

This section analyses the empirical data on the EU’s economic integration, showing a stagnation or decline in economic performance post-integration compared to the pre-integration trend. It highlights how the Single Market failed to boost intra-EU trade or GDP growth; how the eurozone underperformed relative to non-euro EU members and other advanced economies; and how divergence in economic outcomes among member states intensified, contradicting promises of convergence.

2. The euro as an economic and political straitjacket

This section provides a thorough critique of the single currency’s failure, detailing how it strips member states of monetary sovereignty without adequate compensatory mechanisms. It highlights structural issues, such as the inability to manage economic shocks and sovereign debt crises, as well as the euro’s political implications, where the European Central Bank exerts disproportionate power over national governments.

3. The EU’s bias against industrial policy

This section explains how the EU’s restrictive fiscal and state-aid rules inhibit industrial policy. It contrasts this with the success of state-led industrial strategies in other economies like the US and China, emphasising how the EU’s anti-interventionist stance hampers competitiveness and innovation.

4. Beyond structural causes: the EU’s self-sabotage

This section explores how flawed policies amplify the EU’s structural challenges. For instance, the EU’s response to the Russia-Ukraine war, including decoupling from Russian energy, exacerbated industrial decline. Meanwhile, alignment with US-led strategies against China risks further weakening EU competitiveness.

5. Conclusions

The study concludes that the EU’s economic underperformance and political challenges stem from its flawed supranational model, rather than a lack of integration. It contrasts the EU’s rigid framework with looser, multipolar arrangements like BRICS and ASEAN, advocating for a decentralised and flexible approach to intra-European cooperation.

1. The economic performance of the EU so far

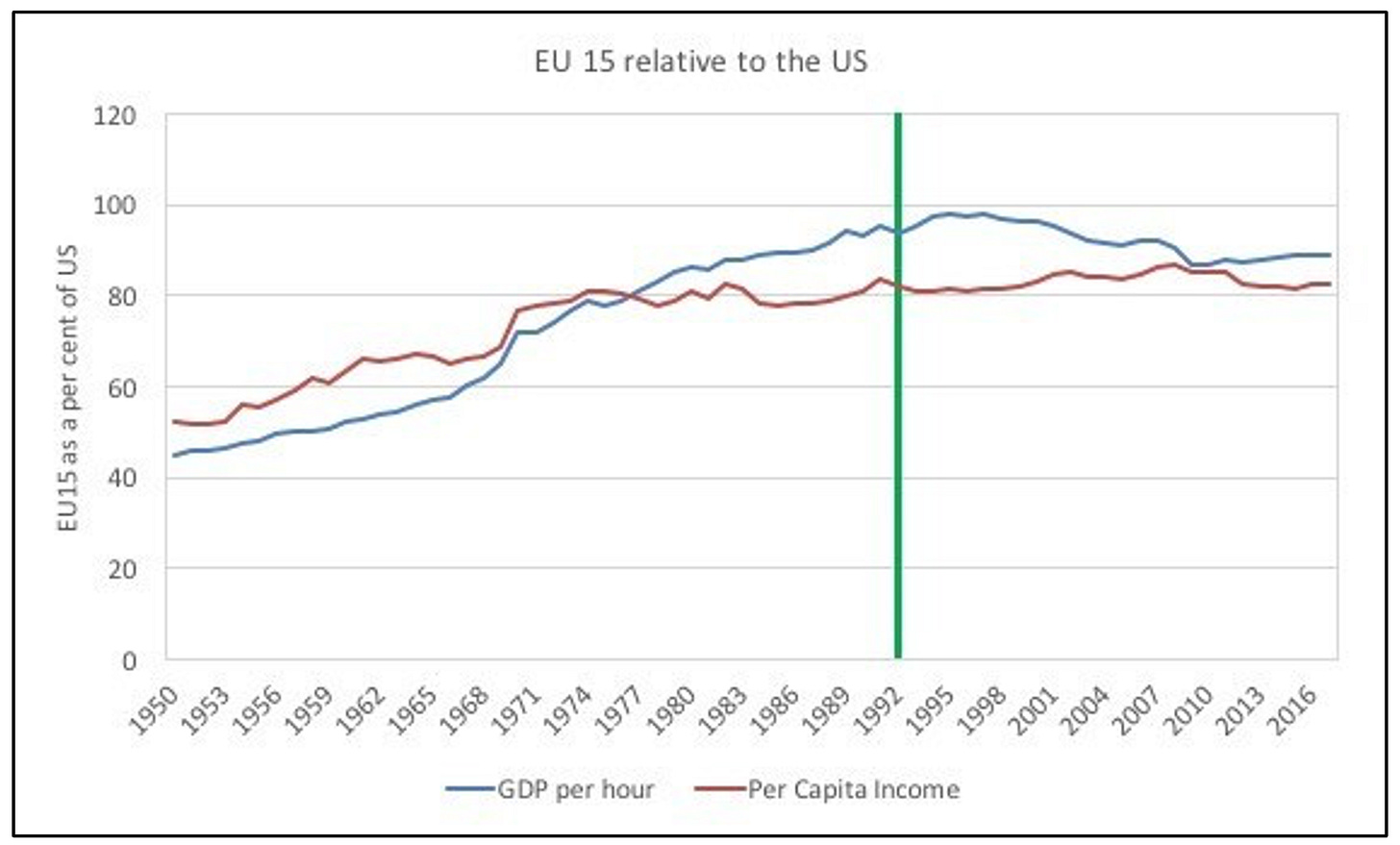

The empirical evidence regarding the process of EU economic integration — beginning with introduction of the Single Market in 1992 — presents a sobering picture. If we compare the GDP per capita of the countries that joined the EU, before and after the introduction of the Single Market, we see that not only did the Single Market fail to improve the EU economies relative to the United States, but would actually appear to have worsened their position.

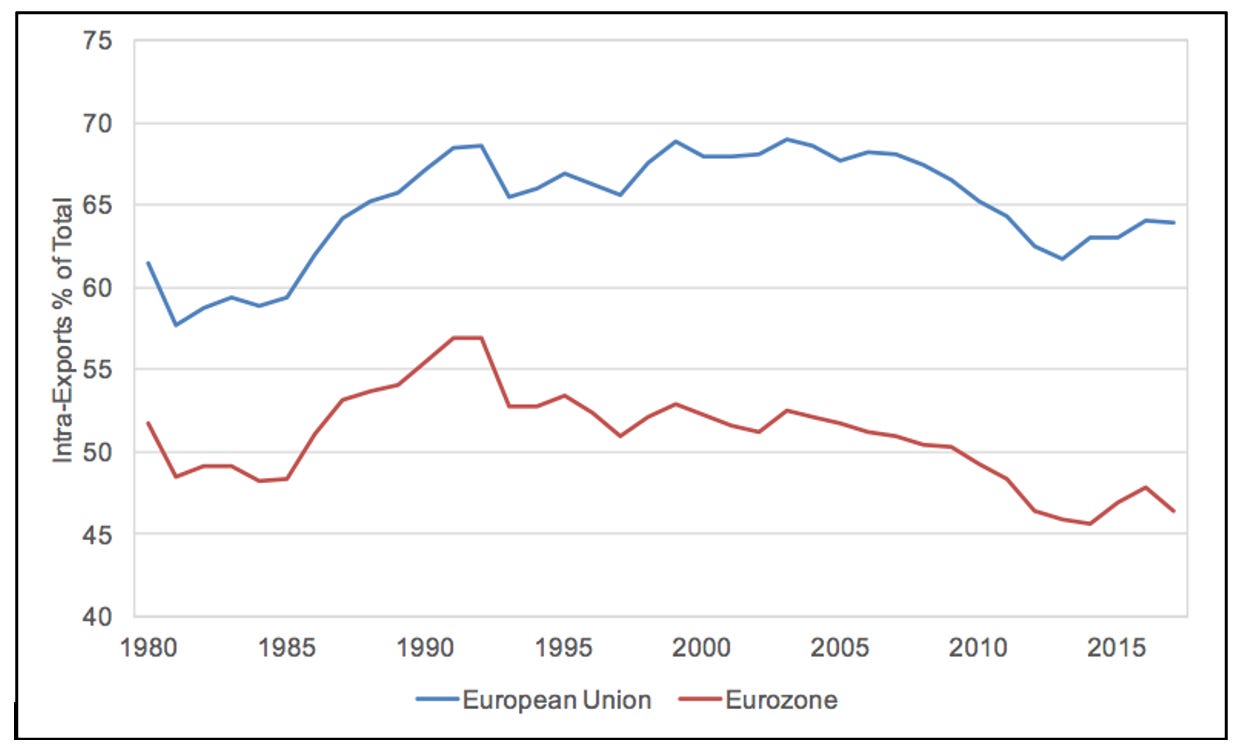

Even more interestingly, the data shows that the creation of the Single Market didn’t even boost trade within the EU, which is particularly striking given that this was the main stated goal of the Single Market. Instead, the proportion of EU countries’ total trade conducted with other EU members, which had risen steadily throughout the 1980s, actually started stagnating following the introduction of the Single Market.

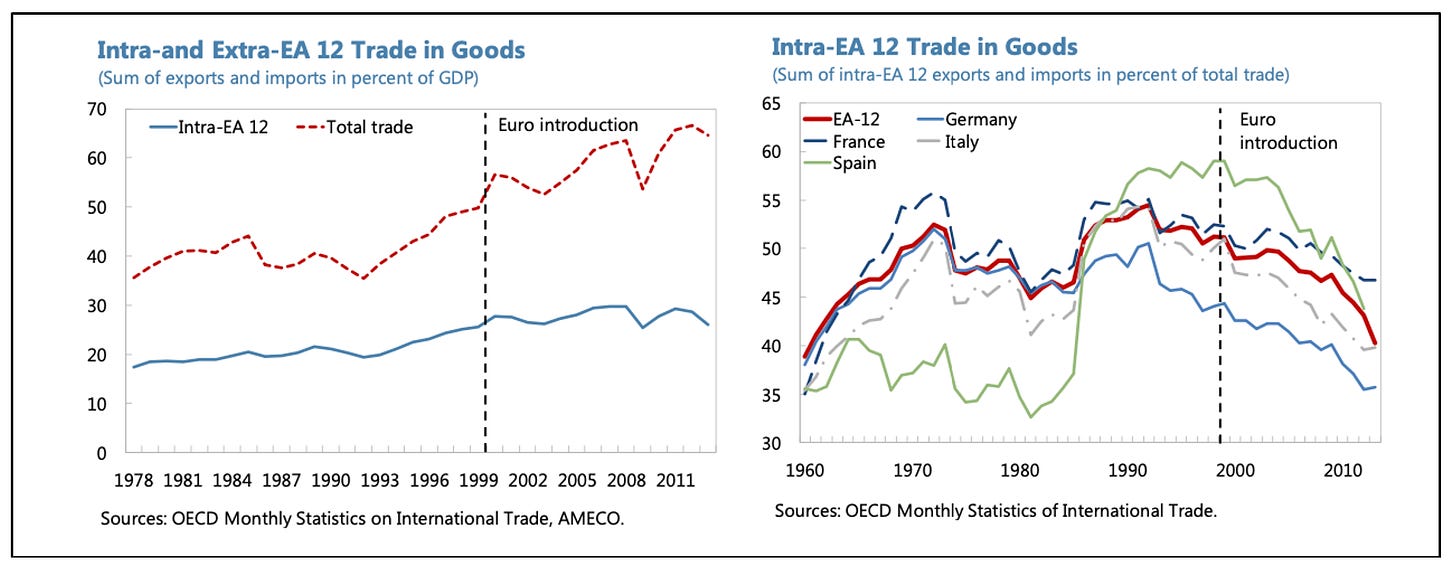

According to the integrationist narrative, things should have significantly improved after the launch of the euro in 2000. Instead, despite predictions that a common currency would substantially boost commerce between member states, by eliminating exchange rate uncertainty and reducing cross-border transaction costs, intra-euro area trade, as a percentage of total trade, has actually been steadily decreasing since then.

This decline accelerated following the global financial crisis of 2008, suggesting that the institutional framework of the EU is particularly ill-suited to addressing major economic shocks. As an International Monetary Fund (IMF) study noted: “Contrary to expectations, there is little evidence that [the euro] has stimulated trade. […] As a share of total trade, intra-euro area trade rose from around 40 percent in 1960 to around 55 percent at the time of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992, but fell back to 40 percent in 2013”.

This has led several studies to conclude that the euro’s influence on trade between member countries has been “zero” — or negative. This outcome fundamentally challenges the economic rationale that underpinned these integration efforts.

The divergence between economic expectations and reality becomes particularly stark when examining GDP performance. The promise of the 1992 Maastricht Treaty was that by giving up monetary autonomy, euro area countries would gain greater economic stability and higher growth, as the elimination of exchange rate uncertainty and lower borrowing and transactions costs, as well as greater fiscal discipline, would lead to more trade, labour and capital flows. Instead, since the euro’s introduction, the eurozone has experienced a marked decline in its economic standing relative to other advanced economies. Real GDP growth in the eurozone, according to World Bank data, has been only 23 percent compared to the United States’ 50 percent, resulting in a significant reduction in the eurozone’s GDP share relative to the US — from 73 to 60 percent.

This performance gap has widened notably during periods of economic stress. The post-financial crisis recovery in the eurozone was notably slower than in the US, and this pattern repeated during the Covid-19 pandemic. While the US demonstrated remarkable resilience and adaptability, implementing swift fiscal and monetary responses, the EU’s recovery, on both occasions, was hampered by institutional rigidities and policy constraints inherent in its structure.

One might argue that things would have been even worse without the euro. While that is possible, this claim becomes difficult to defend when considering that European countries outside the eurozone, such as Poland and Sweden, or even non-EU countries like Norway, navigated both crises far more successfully than many eurozone members. In fact, as we will explore, there is substantial evidence suggesting that the EU’s poor performance was not in spite of the euro but because of it.

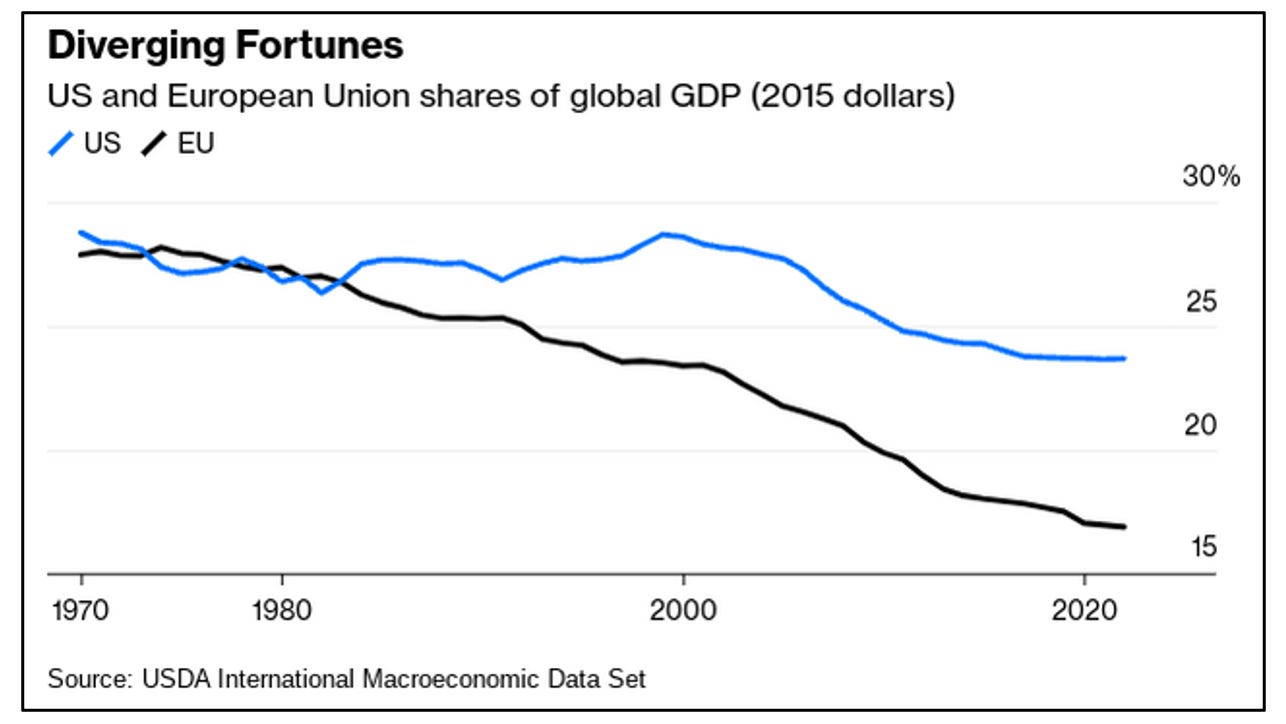

The EU’s economic performance relative to the US has worsened dramatically since the outbreak of the Ukraine war. Economic growth in the EU has been slower due to the (largely self-imposed, as we shall see) energy crisis, high inflation and weakened industrial competitiveness. Some EU economies have faced near-recessionary conditions, with countries like Germany experiencing a significant slowdown, or even outright deindustrialisation, due to dependence on energy-intensive manufacturing sectors.

The implications of this divergence extend beyond relative economic performance. The EU’s share of global GDP has contracted from 27 to 16 percent over the past thirty years, while the US has remained stable at around 25 percent, reflecting not just underperformance relative to the US but also a broader loss of economic influence in the global economy. As Bloomberg columnist Adrian Wooldridge noted: “America’s share of global output still hovers not far from what it was in 1980. Europe rather than the US is paying for the rise of Asia in terms of a diminishing share of global GDP”.

This decline raises fundamental questions about the effectiveness of the EU’s economic governance model and its capacity to maintain European competitiveness in an increasingly multipolar world order.

The euro’s impact on economic convergence among member states reveals another significant failure of monetary union. Proponents argued that a single currency would naturally lead to economic harmonisation, and to a greater convergence in economic performance and living standards. The reality, however, has proven quite different. The divergence in prosperity levels between member states has actually widened since the introduction of the euro, with countries like Germany and Italy experiencing markedly different economic trajectories.

This divergence manifests in several key metrics. While there has been some nominal convergence in areas like inflation rates and interest rates — abruptly interrupted when the euro crisis broke out in 2011 — real economic indicators tell a different story. Real GDP per capita differences between member states have expanded rather than contracted. As the aforementioned IMF study notes:

The euro area crisis has tested the stability of the euro area and exposed trends of economic divergence. Moreover, the positive effects of economic union on trade, labour mobility, and productivity have been weaker than expected, while cross-border capital flows materialized, but served as a destabilizing force.

A 2017 study by the Centre for European Policy in Freiburg tried to quantify the benefits (and losses) for individual nations. It concluded that, out of the examined eurozone countries, only Germany and the Netherlands gained from the euro. Germany is by far the country that gained the most: almost €1.9 trillion between 1999 and 2017. This amounts to around €23,000 per inhabitant.

In all the other countries analysed, the euro resulted in a drop in prosperity over this period, most notably in France and Italy. In Italy, the introduction of the euro led to a loss in prosperity of around €74,000 per capita or €4.3 trillion for the economy as a whole from 1999 to 2017. For France, the loss for the same period amounted to almost €56,000 and €3.6 trillion respectively.

The euro, however, didn’t simply fail to promote economic convergence; it actually put a stop to the income convergence witnessed in the decades leading up to the Maastricht Treaty. In the per-Maastricht period, there was steady income convergence across future euro area countries. However, contrary to expectations, income convergence among eurozone countries actually slowed after Maastricht and subsequently came to a halt. Divergence under the single currency was witnessed in other areas as well, such as productivity and unemployment rates. In other words, the euro promoted divergence across the board. More recently, this trend of divergence has persisted, albeit with reversed roles: in 2024, peripheral economies such as Spain, Portugal, and even Greece experienced modest levels of growth, while the EU’s largest economies, Germany and France, remained stagnant.

The same dynamic is witnessed among latecomers to the euro: countries that joined the euro area in 2007 or later experienced continued convergence in the run-up to their accession, with income differences between “old” and “new” euro area members narrowing substantially prior to EU and euro area accession of the latter group. However, convergence for these countries has also slowed since the financial crisis. Meanwhile, countries that did not join the eurozone and apparently have no near-term plans for doing so — such as the Czech Republic, Hungary and Poland — have steadily converged towards living standards in higher-income European economies.

The claim that the euro would promote the development of value-added chains across the Single Market has also not materialised. Notably, Germany’s most extensive value-added chains developed with non-euro countries, which experienced the most rapid growth in trade with Germany. A 2014 ECB report on global value chain participation among OECD (Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development) and non-OECD countries reinforces these findings. Among the top twenty OECD countries in global value chain participation, nine were outside the eurozone and/or the EU, and they were not members of other monetary or trade unions. Equally noteworthy is the observation that the participation rate of non-OECD countries, many classified as “developing”, was only marginally lower than that of the most industrialised nations.

Finally, did the euro succeed in its aim of becoming a credible alternative to the dollar as an international reserve currency? The evidence suggests it did not. Contrary to expectations of monetary power and currency prominence, the euro’s share of global usage remains approximately equivalent to the combined use of the national currencies it replaced before 1999. In other words, no significant transformation has occurred. As reported by the ECB, the euro accounted for only 20.5 percent of global official foreign exchange reserves in 2022, compared to 58.4 percent held in US dollars. This limitation reflects both the fragmented nature of eurozone financial markets and the broader stagnation of the European economy.

In summary, if we evaluate the euro against its primary stated objectives — boosting intra-EU trade, promoting economic growth and employment, reducing divergences between member states, fostering value-added chains, and establishing itself as a credible competitor to the dollar as an international reserve currency — it is evident that these goals have all been missed. On the contrary, trade integration has fallen short of expectations, economic growth has stagnated, and instead of fostering convergence, the euro has exacerbated economic divergence among member states, creating a dynamic of winners and losers rather than delivering equitable benefits. Overall, the euro has been an unmitigated failure.

This can only lead to one conclusion: to extent that that euro is an integral part of the EU project encompassing most member states, its failure reflects a broader failure of the EU itself. Indeed, the euro is a significant — though not exclusive, as will be discussed — factor in explaining the EU’s underwhelming economic performance. This is especially true when considering the way in which the stagnation in GDP growth and productivity across the EU has resulted in a broader lack of dynamism and competitiveness of the EU economy.

In his report published last year, Mario Draghi painted a dire picture of the state of the European economy. According to the report, the EU is underperforming in several key areas compared to other major economies, particularly the US and China. The report emphasises that the EU faces a persistent “innovation gap” due to a “static industrial structure with few new companies rising up to disrupt existing industries or develop new growth engines”, limiting investment in new tech sectors compared to the US, which has fostered dynamic sectors like AI and cloud computing. More in general, the study notes that the EU is stuck in a cycle of “low industrial dynamism, low innovation, low investment, and low productivity growth”.

The Draghi report identifies several causes for the EU’s structural lack of competitiveness, one of the main ones being the EU’s chronic shortfall of productive investment, both public and private, which has created a persistent investment gap between the EU and the US, exacerbating the EU’s slower economic growth. The EU particularly falls behind in innovation and research and development (R&D) spending, limiting the EU’s competitiveness in high-tech sectors. EU R&D expenditure is lower than in the US and Japan, with few member states reaching the EU’s 3 percent of GDP target for R&D investment. But the Draghi report falls short of adequately explaining why the EU has failed to invest in the economy. The reason is obvious: doing so would have meant admitting that the main cause of the EU’s structural underinvestment is… the EU itself, and especially the single currency.

In the second part of this study we will look at the euro as an economic and political straitjacket, detailing how it strips member states of monetary sovereignty without adequate compensatory mechanisms. It will highlight structural issues, such as the inability to manage economic shocks and sovereign debt crises, as well as the euro’s political implications, where the European Central Bank exerts disproportionate power over national governments.

Thanks for reading. Putting out high-quality journalism requires constant research, most of which goes unpaid, so if you appreciate my writing please consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you haven’t already. Aside from a fuzzy feeling inside of you, you’ll get access to exclusive articles and commentary.

Thomas Fazi

Website: thomasfazi.net

Twitter: @battleforeurope

Latest book: The Covid Consensus: The Global Assault on Democracy and the Poor—A Critique from the Left (co-authored with Toby Green)

Well written and interesting essay. In the United States during the 1830s, the nation consciously stood at a fork in the road between two radically different state formation logics. One was the Henry Clay style “American System,” which aimed to bind the continent by imposing continental divisions of labor, aligning each region to a specialized economic role, coordinated by powerful centralized institutions, national credit, and elite policy‐making networks, in short, economic central planning. The other was the Jacksonian republican path, a multi-tiered, federated system that diffused economic and political power downward, cultivated redundancy across all spheres (economic, scientific, institutional), preserved local agency and institutional pluralism, and “bound” its vast territory not by forced specialization but by creating many centers of productive power all actively trading with one another. This produced both cohesion and dramatically higher broad-based economic dynamism without collapsing sovereignty into one central node. Unfortunately, this was largely nullified by a set of actions and changes in the post WW2 decades. But beneath the surface there are signs that the ghosts of the past may be stirring.

Also unfortunately, and relatedly, post WW2, and then, more importantly, post advent of Globalization, Europe unfortunately chose (or, I should say, the European peoples had it chosen for them) to pursue something much closer to the former, not a genuine federated system, but a technocratic, centralized arrangement whose internal logic more closely resembled the late Austro-Hungarian Empire, centrally coordinated economic blocs, harmonized regulations, and policy spheres designed to suppress political variability in the name of “integration.” Thus, the project carried a structural rot from the beginning, and when it finally got into the air with enactment of the Schengen and the Lisbon treaties producing dependency, vulnerability to shocks, and democratic brittleness, because it internalized the very logic of managed continental division of labor that Jacksonians had rejected in the 1830s as unfit for a truly democratic, pluralistic polity

Before the Euro, Germany had a strong currency (the Mark), France had a less strong one, and Italy a weak one, subject to frequent devaluations. A good analogy is that of shoes : with the Euro, all countries must run the race with the same size of shoes. So the shoes are a perfect fit for Germany; much too small for France and even smaller for Italy... Unsurprisingly this doesn't work equally well for every country.