Germany’s authoritarian turn

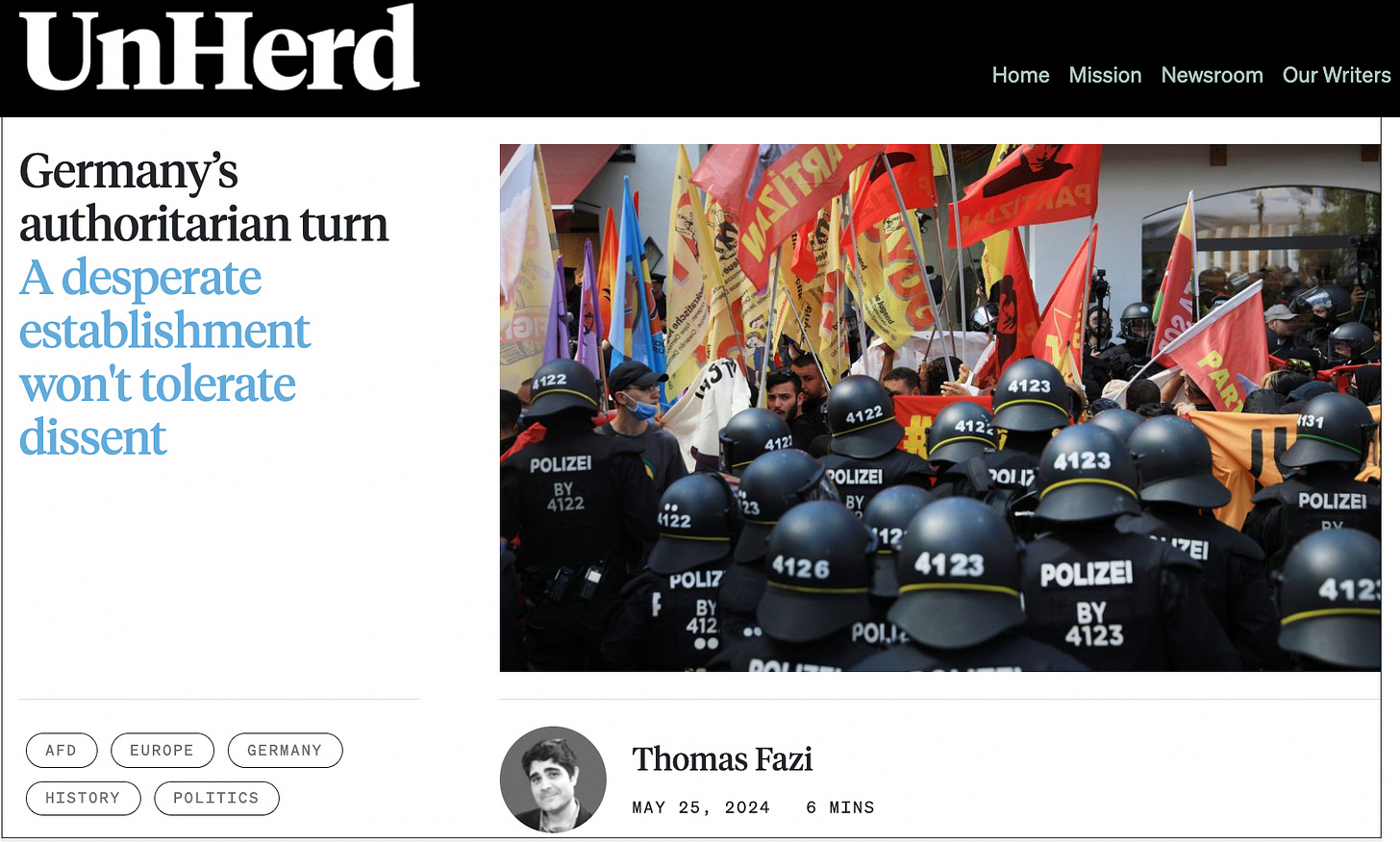

An increasingly desperate establishment is cracking down on dissent, both on the right and on the left

I’ve written for UnHerd about Germany’s descent into rampant authoritarianism as the government cracks down on free speech and dissent on the right and the left alike — and how it relates to the anti-democratic foundations of the country’s constitution, based on the idea that the status quo must always be protected from the “excesses” of democracy:

It would be comforting to see [the current authoritarian turn] as a betrayal of German post-war democracy and of its institutional bedrock, the constitution of 1949, or Basic Law — not least because it would imply that this is an awkward deviation from the norm, which may be potentially corrected by appealing to the strong democratic safeguards offered by that very constitution. Indeed, this quasi-religious faith in the constitution is deeply engrained in the German post-war collective consciousness, not just among intellectual elites — Habermas and others developed the concept of “constitutional patriotism” — but among dissidents as well: during the pandemic, it was common for protesters to hold up a booklet of the constitution as a symbolic shield against state repression.

But what if the current authoritarian turn in Germany is not a failure of the constitution but rather a case of it doing exactly what it was designed to do? The German constitution has long been seen as the country’s main democratic bulwark against the kind of anti-democratic aberrations of the Nazi era. However, for its creators, this meant, paradoxically, that it also had to act as a bulwark against democracy itself — or better, its potential “excesses”. After all, as liberal commentators never tire of reminding us, Hitler rose to power through democratic means. As the weekly newspaper Die Zeit recently observed, the Basic Law is “deeply laden with scepticism” and mindful of “the abuse of power and the obstruction of the democratic system”. Its creators didn’t trust the people, and were actually quite fearful of the concept of mass democracy.

They thus took it upon themselves to create a constitution that, while guaranteeing equal individual rights for all citizens, would also contain various safeguards and provisions to ensure that the “will of the people” would not get out of hand.

Once one understands the ideological premises of the German constitution — that the state must do whatever it takes to protect the status quo from any threats arising from the masses — the nation’s authoritarian turn starts to make sense. Far from being an aberration, this is exactly what the German post-war system was designed to do all along.

Read the full article here. If you’re a paid subscriber and you can’t access the paywall write to me at thomasfazi82@gmail.com.

Thanks for reading. Putting out high-quality journalism requires constant research, most of which goes unpaid, so if you appreciate my writing please consider upgrading to a paid subscription if you haven’t already. Aside from a fuzzy feeling inside of you, you’ll get access to exclusive articles and commentary.

Thomas Fazi

Website: thomasfazi.net

Twitter: @battleforeurope

Latest book: The Covid Consensus: The Global Assault on Democracy and the Poor—A Critique from the Left (co-authored with Toby Green)

If I remember well, the Grundgesetz should have been replaced by a constituition at the Wiedervereinigung. Didn't happen.

The German system was set up to prevent popular sentiment from taking effect quickly, that's true. In the past, authoritarian features came to bear to basically keep a course and pursue policy against majority opinion, as per - but this one feels different.

From migration to energy price to deindustrialisation, there is no course, no policy, apart from the usual background grift and corruption that comes with government funding.

All the effort seem to be directed to afford the elites to deny reality, retreat into a fantasy world and govern that.